Where Have All the Truckers Gone?

Photo: Getty Images by Michael Godek

Driver shortages, crowded ports and unreliable service are causing major ground-shipping anxiety—and that's before you even get to the self-driving trucks.

How concerned should we be?

Share This Story

by Brendan Menapace

July 2019

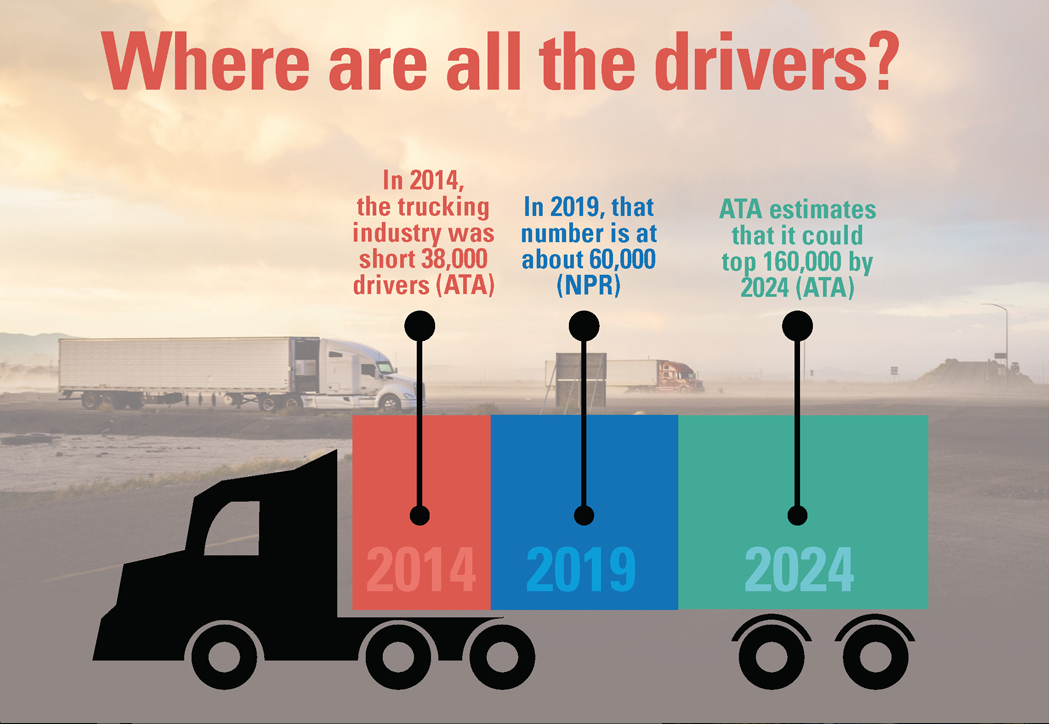

There’s been increasing concern over an impending shortage of truck drivers in the U.S. Trucking companies have adjusted pricing and wages to become more appealing to potential drivers, but it appears to be a losing battle. The numbers don’t look good. American commerce depends on trucking, and the promo industry, with its complex supply chain and customers who often need orders fast, does too.

According to an NPR piece published in February, the American Trucking Association estimated that the U.S. trucking industry is currently short by about 60,000 drivers, and that number could rise to as high as 100,000 in a few years. Bob Costello, chief economist at the ATA, said last year that the shortage was “a demographics problem,” and blamed the aging workforce and lack of female drivers as the key components to the shortage. NPR reported that currently only about 8 percent of truck drivers are female.

To combat the problem, trucking companies have done their best to make wages more appealing to potential workers and make prices more appealing to customers. Gordon Klemp, president of the National Transportation Institute, told NPR that trucking companies increased their pay by 10 percent on average, making the average driver’s salary about $60,000. The problem is that it’s not just about the wages. “If you’re not getting a 401(k), health care, paid time off, you need to get a different job, because you can get all of that [elsewhere],” Costello told NPR.

Even with companies offering perks like signing bonuses, education help, referral bonuses and other monetary incentives, companies just haven’t seen the results they want. “Everyone around us is in need of more drivers,” John Roberts, supervisor of Philipp Trucking, told KCRG in June. “I could use 10 truck drivers right now.”

A new initiative from the U.S. Department of Transportation would allow those aged 18 to 20 serving in the military to skirt a current law that states that you have to be 21 to be a commercial truck driver. As long as those military members have a military equivalent commercial driver’s license to drive a truck on the interstate, they would be eligible to take these jobs.

Clearly, there is an issue here, and it’s something that both trucking companies and the trucking industry’s governing bodies have noticed. But how has it affected the promotional products industry? How concerned should we be?

That sort of depends on who you ask.

Extent of the problem

When someone hears that there’s a driver shortage and sees the various doom-and-gloom projections and impassioned pleas from trucking authorities for more workers, the first thought is likely, “Oh no, this is bad!” And that’s not wrong. But, it’s also not the only way of looking at the situation.

For Steve Bogart, senior vice president of Blue Generation, Long Island City, N.Y., his company’s strategic location in the New York City metropolitan area means that access to freight trucks is never an issue. There will always be truck drivers coming to New Jersey. What it also means is that the variables and uncertainty within the trucking industry has caused trucking companies to compete against one another, giving Blue Generation the option of paying less than they otherwise might have with a fully-staffed nationwide fleet.

“We have seen an increase in competitiveness in the trucking business,” Bogart told us. “Whenever we have truckloads to different parts of the country, we get quotes from several carriers to compete for the best rate. We are a sought-after account because many of our shipments go across the country to California and in between. They are usually large shipments. Even if we have an LTL [less than truckload], they are anxious to get our business. It’s been very competitive. I have people knocking at the door saying [things like], ‘I’ll give you 82 percent off published trucking rates.’”

Bogart noted that within the last year or so, he’s seen companies that otherwise haven’t really budged on their prices start joining the fight for business and being more flexible with offering discounted rates. He added that, on average, the shipping rates he’s seeing are basically all discounted rates. That doesn’t mean that Blue Generation just goes with the cheapest option. Like anything in the world, you tend to get what you pay for, so the supplier still looks for reliable options at a good price. But the appeal of its business and the constant presence of shipping options in a major city like New York allows it to look for bargains that might not be available to others in more rural, decentralized locations.

“I think it mostly has to do with the pickup location,” Bogart said. “If you pick up in a low-volume, low-population area that doesn’t get much business, there’s not going to be many choices, and probably aren’t going to be many drivers who want to go there. But, if you’re in a high-volume area like our warehouse in New Jersey, there are a lot of [shipping options]. We’re in a better position.”

Still, not every supplier or distributor is in a high-volume location. And some promo companies in lower-volume areas have noticed issues. A representative of one such supplier told us he’s seen a major dropoff in reliability, pointing to the driver shortage as the primary reason. “Apparently, they’re retiring in droves,” he said. “This is a very serious problem that makes us suppliers look like the bad guys, but we have no control over the freight companies. And it seems to be getting worse.

“Just this week, and this is not an isolated case, we had a best quote from a pool of a half-dozen carriers with FedEx Freight at the best price for a delivery for a large order for a longtime customer that needed the product delivered yesterday,” he continued. “Upon tracking the shipment after pickup on Friday, they said they couldn’t make the originally promised Monday delivery and it would be Tuesday. It might as well have been next week. And this is FedEx Freight, but then Land-Air, Roadway/Yellow Freight, Canadian Freight and a host of others have pulled the same stunts or have even been days late on the pickup with no apologies or refunds.”

When we first looked into trucking issues in 2018, Curtis Grotting, vice president of logistics for The Magnet Group, told us that he was also aware of the situation. Grotting said drive times were increasing and driver numbers decreasing as new standards reshaped the way trucking companies can do business.

"The primary issue has been the congressionally mandated rule requiring all drivers to follow the new Electronic Logging Devices (ELD or Electronic Log) in all truck equipment," Grotting told Promo Marketing at the time. "This is a transition from drivers being able to manually fill out their logbooks (allowing for drivers to have more flexibility in cheating the system), to an electronic device that tracks and ultimately will fine a driver or the company he works for if they are not adhering to the driver safety standards."

Foreground image: Getty Images by RaStudio

What can we do?

Last year, Grotting said that suppliers were attempting to counter trucking issues in a few ways—faster production times to offset shipping delays, LTL shipping services with more reliable transit schedules, smaller parcel carriers like UPS or FedEx, etc. But all of those have downsides.

Another option might be investing in and cultivating better relationships with trucking companies and other service providers. This is where Anthony Nicacio, warehouse manager for ALPI International, Oakland, Calif., says his company has excelled. ALPI has had a strong relationship with its transportation supplier for a few years now, and it’s been mutually beneficial. ALPI gets to work with a reliable company that it’s comfortable with, and the shipper gets the steady business.

“Our relationship with our trucker was built over time with him continuously coming by the warehouse and attempting to get our business, which at one point he had better rates than our previous truckers, so we made the switch to him,” Nicacio told Promo Marketing. He added, though, that while ALPI hasn’t seen too much of a problem due to the reported driver shortage, he has noticed rates climb a little. But he thinks the problem lies more in ports like the one in Oakland, rather than specifically with the trucking industry.

The ports have been their own animal lately. Overcrowding and other issues have caused massive backups at ports like Los Angeles, Oakland and New Jersey. In 2014 and 2015, a string of work stoppages kept shipments from being unloaded for long periods of time. In 2016, the financial collapse of South Korean shipping company Hanjin left one of the terminals at the Port of Long Beach in a standstill for months, causing cargo volume to drop significantly. During that same time period, the Port of Los Angeles saw an increase in cargo volume, which clogged up the whole operation.

“I would like to note that our driver has seen an increase in time he is spending at the port while he picks up our loads,” Nicacio said. “Our driver has informed me of multiple times he sat inside the port for hours at a time, only to not be able to get our shipments and have to come back the next day and repeat the same thing. In my personal opinion, I believe the problem lies within the port and how they are running their operations, causing longer wait times, misplacement of containers. And I honestly don’t think they really care for the customer at the Port of Oakland.”

Consolidation and reform in the international shipping community, namely with Chinese companies, caused record-low growth in 2016, close to 0 percent in comparison to the usual 7 or 8 percent. What that meant, in some cases, was a drop in shipping rates due to companies trying to stay competitive. For trucking, the issue hasn’t been that companies are buying up one another (like we saw in China’s international shipping industry over the past few years), but the lack of people actually working at the companies, which has caused companies to drop their prices in the hunt to stay afloat. If a lack of human resources is the heart of the issue, then, there may be a solution coming.

What if we don't actually need people anymore?

That seems like a weird, misanthropic question to ask, but it’s a legitimate one. What if the solution to the shortage of people in the trucking industry is to forget people all together? That is to say, what if the self-driving trucks that Elon Musk and others have promised really are the answer? Major companies like Walmart, which just inked a partnership with Gatik AI, a self-driving delivery van startup, are already using them. There are also rumblings that Ford is proposing an autonomous mail truck service to the USPS, which has had its own share of delivery and staffing problems in recent years.

Matthew Klein, a journalist for Barron’s who has covered the driver shortage extensively, believes the overall issue is overblown. Klein says that if the shortage was as bad as the ATA and other organizations are reporting, hourly wages in the trucking sector should be rising faster than they are. And while he notes that trucker wages have indeed grown rapidly since 2018, he believes that is simply compensation for wage stagnation at various points from 2016 to 2018. He also takes issue with the ATA’s Truck Driver Shortage Analysis report.

“The report is vague about its methodology, simply asserting thata shortage exists and will get worse over time as demand rises and existing truck drivers retire,” Klein writes in an article for Barron’s. “While turnover at many trucking companies is high, the ATA notes this is mostly caused by ‘drivers moving from one carrier to another.’ Meanwhile, the ATA’s most recent compensation survey suggests that driver pay is rising at a rate comparable to that of workers in the rest of the U.S. private sector.”

But Klein told Promo Marketing that self-driving trucks could be a major solution for trucking companies looking to boost their staff or speed up delivery times. “I am not an expert on the subject, but based on my reading, I think self-driving trucks have significant potential to benefit shippers,” Klein said. “Algorithms do not need to stop for food or sleep, which should reduce transit time sand allow truck owners to get more use out of their vehicles.”

He added, however, that it could create a new headache for companies, as the value of the trucks themselves would depreciate faster due to spending more time on the roads. But, overall, if the technology is there, it could be a safer and more efficient method. “Self-driving vehicles could also end up being safer than human-driven trucks because they cannot get tired or distracted,” he added. “However, the technology has not yet advanced that far. It is not clear when it will, or if it ever does.”

Klein said that until that technology reaches the point where it is safer than (or at least as safe as) human drivers, the industry will still rely on people, at the very least to sit in the self-driving truck as a backstop. That could negate the potential savings self-driving trucks would create in the first place. And, once they get to their destination, there would likely still be the need for humans to handle the loading and unloading phase.

For Jeff Becker, president of Kotis Design, a distributor based in Seattle, however, the promise of self-driving vehicles is intriguing. Becker believes that it is the future of not only decreasing pricing for shipping, but decreasing time, fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Being in Seattle, Becker is all-too familiar with big tech companies like Microsoft, and, as a Tesla driver himself, he’s seen firsthand what the future of automobiles can do to disrupt entire industries.

“I think self-driving trucks will be insanely beneficial for the whole world,” he said. “People are concerned that self-driving trucks are going to put truck drivers out of work, but there’s not enough truck drivers as is. It’s hard to put someone out of business when you can’t hire someone already for it.”

He echoed what others have said, in that the main problem self-driving trucks solve is the issue that human beings physically can’t stay awake long enough to drive for days at a time. With self-driving trucks, that would no longer be an issue.

“I don’t know what the rule is. Maybe a truck driver can drive 12 hours in a day,” he said. “With a self-driving truck, you put five trucks back-to-back-to-back-to-back, and the driver sits in the front. Two drivers can take a series of five trucks and drive for far longer than 12 hours.”

As Klein brought up, however, you’d still have the problem of having to pay workers to sit in the cab as the human backstop while the truck drives itself. And Becker admitted that as truck drivers are more in-demand, wages for those jobs should continue to rise. Companies would still need to pay those people to sit in the trucks. The secret to staying in the black, in his opinion, is to go a step beyond just self-driving trucks and move toward fully electric vehicles.

“Now you’re not going to be paying for fuel,” he said. “I have to imagine the two main expenses here are humans and fuel. If you can take out the human element and you can take out the fuel element, not only are the costs going to go down, but freight can get there quicker.”

Becker used the example of his own company’s facility in Utah. Right now, it takes two days for Kotis Design to ship products from Utah to its headquarters in Seattle. Utah is centrally located for a lot of western U.S. destinations like Denver, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Seattle and more, opening up the possibility of faster shipping to a ton of clients. And if Amazon’s dominance in the marketplace has taught us anything, it’s that people want things fast.

“It is a two-day ground shipment [from Utah to Seattle],” Becker said. “I believe that in the coming years, self-driving trucks will turn my two-day ship from Utah to Seattle from two days to one day. A truck driver cannot make it by himself or herself [in that time period]. They cannot make it within one day based on limitations with driving hours. I believe a self-driving truck can make it in one day.”

Self-driving technology seems to be moving at a rapid pace, thanks to companies looking to minimize the costs that Becker mentioned, as well as taking safety into account. It doesn’t mean that robot overlords are going to rise up and use human beings as batteries, keeping us docile in a computer-generated reality that eventually we break out of and destroy. That’s sci-fi stuff straight out of “The Matrix.” But it does means that trucking companies will certainly be looking into self-driving options. And, for promotional companies that rely on ground shipping on a regular basis, it’s time to warm up to the idea of changes within the shipping space. In Becker’s words, it’s not a matter of if it’s going to happen, it’s just a matter of when.

In the meantime, until that technology reaches a point where self-driving, electric trucks are zipping all over U.S. highways in record time, companies need to figure out ways to handle their own business. The future seems fun, but today, all signs point to a trucking industry that has real trouble staying staffed and handling demand.

If you’re in a major metropolitan area, like Blue Generation or many other promo businesses, you can use that to your advantage and let the the fundamentals of capitalism drive prices down as the abundance of shipping companies working in the area compete against one another, dropping their prices lower and lower. If you’re in a more rural, lower-volume location where the number of companies that come through isn’t as high, you can focus on creating a relationship with your transportation supplier to maximize cost and efficiency as much as you can.

And, if you’re looking to the future for the solution to all of 2019 America’s problems, you can hope that it works out the way you want.